The end for V-2 troops of Division z.V. (Division for Retaliation) came

in April of 1945. Everywhere in the Germany the fires were burning. It

was a signal of the incessant and unstoppable penetration by enemy forces

from the east and west. The retreating Germans formed up to fight against

the Allies, having been rallied by fanatical commanders still sworn to

Hitler. However, in the end, the soldiers submitted to the overwhelming

Allied supremacy, usually without much resistance. Berlin had been surrounded

for days, and somehow the German war effort continued—even as the Allies

rolled across Germany. Hitler had ordered a breakthrough to rescue Berlin

from the Russians who were squeezing the city. The orders received by the

German commanders were impossible to carry out, as it was no longer possible

to amass effective combat-ready troops. When the orders were given this

plan was already an illusion.

On the evening of March 23, 1945, British troops under Montgomery had reached

the Rhine River, and several days later, the situation for the V-2 troops

in Holland became critical. The German High Command ordered the immediate

withdrawal of all troops and material related to both the V-1 and V-2 operations

in Holland. Battalion 485 (Art. Reg. 902). Protected by low clouds on the

rainy Thursday afternoon, they drove in a long procession to Leiden, from

there to Utrecht, and then finally to the German border. Equipment removed

from the firing sites was littered along the route as fuel ran out and

chain of command broke down. They arrived in the area of Fallingbostel

on April 1, 1945, and were joined there the following day by the second

battery. A few days later, the majority of the battalion’s specialized

vehicles and equipment, along with some remaining rockets, were destroyed

haphazardly with explosives at a large outdoor storage area for V-2s near

Leese, northwest of Hannover in the Hahnenberg Forest.

The SS Werfer Battery 500 had been firing on Antwerp from sites near Hellendoorn

in Holland. During the last days of March, some of the platoons were given

a quick course in close-combat infantry training. Being completely cut

off from outside news, the soldiers could only guess as to why this training

was given. On the nights of March 27–30, the whole battery packed up and

withdrew from Hellendoorn because of advancing Canadian forces. Each platoon

left the launching area on different nights using different routes, but

all went in the general direction of Nordrhein-Westfalen. They took everything,

including excess rockets and all battery vehicles, moving under the cover

of darkness. As the units traveled through Lingen, Niederdorf, Lemke, and

Nienburg, the firing crews thought it was a normal firing position change.

The soldiers would only find out days later that the SS 500 had been ordered

to move east in defense of Berlin. On April 1, some of the platoons arrived

at Dorfmark just north of Fallingbostel, 23 miles north of Hannover.

In the area of Fallingbostel the men of the SS 500 were split up into new

groups. Some received new combat assignments, while most formed the nucleus

of several new Nebelwerfer artillery batteries. The 15-centimeter Nebelwerfer

41, or Screaming Mimi as American soldiers called it, was an artillery

piece that fired solid-fuel rocket projectiles. The weapon was designed

to saturate a target with spin-stabilized smoke, explosive, or gas rockets.

A large portion of SS 500 soldiers chosen for the new batteries was previously

trained as artillery men prior to their V-2 deployment. The artillery pieces

were brought in from the Nebelwerferschule (Nebelwerfer School) at Celle,

and a quick training program was instigated by elements of the SS Werfer-Lehrabteilung.

On April 5, most of the specialized V-2 equipment and vehicles belonging

to the SS 500 were demolished to prevent their capture by the Allies. However,

the Feuerleitpanzer halftracks belonging to the platoons were converted

into combat vehicles by cutting the armored top section away and fitting

them with twin 20-millimeter guns.

At the beginning of April Training and Experimental Battery 444 had driven

to the village Steinhorst where a portion of their equipment was demolished.

Some of the men formed up with orders to join the V-2 division and fight

the Allies as infantry, but a larger part of the men were tired of the

war and deserted to the north. These men arrived at a place called Welmbüttel

in Schleswig-Holstein. The remaining rockets and specialized vehicles,

such as the Meillerwagen, were towed into the bog at Welmbüttel and

demolished with explosives. Some of the soldiers took quarter in nearby

villages and reportedly stayed there until the war ended.

Battalion 836 (Art. Reg. 901) had been idle for several weeks. Having launched

their last rocket from the Hachenburg area on March 16, 1945, they spent

the last days of the month packing and shipping excess rockets and equipment

out of Hachenburg because of the lack of liquid oxygen and the Allied breakthrough

at Remagen. They received word to gather at Bramsche, about ten miles west

of Osnabruck, for further orders. The deterioration of the basic military

situation, however, prevented this. Instead, the battalion was ordered

to the area of Visselhövede for the Blucher Undertaking. From there,

their remaining rockets were to be fired against the Küstrin Fortress

in Poland. Over the previous two weeks, Stalin’s forces had advanced roughly

100 miles from the Baltic, near Kolberg in Pomerania, to the Oder fortress

of Küstrin, about 60 miles northeast of Berlin. The plan fell apart

because of the total breakdown in Germany. On April 3, 1945, Hitler ordered

that no more explosives were to be used for V-2 warheads, thus terminating

the offensive once and for all. As a result, all of Group South’s equipment

was destroyed on April 7, 1945, in the area of Celle to prevent its capture

by the Allies.

On April 6, 1945, as the British forces approached the Weser River, chaos

was everywhere. The German units were disorganized and communications were

nonexistent. Near Stolzenau some of the excess SS 500 personnel, along

with a battalion of Hitler Youth and a company of inexperienced German

engineers, were ordered to fend off enemy tanks with only small-arms fire

and a few 88-millimeter flak guns. Tanks of the British Second Army attempting

to cross the river were eventually turned back but crossed later at Petershagen,

south of Stolzenau. The tanks headed north to meet up with a British commando

brigade near Leese, where on April 8, abandoned and demolished V-2s were

discovered on flatbed railcars and in the forest just outside a chemical

manufacturing plant. Kampfstoffabrik Leese was one of a number of secret

plants built in this area of to produce chemicals for the German war effort.

Since February of 1945, there had been a plan by Gruppenführer Hans

Kammler to convert the V-2 launching units into a normal motorized combat

division. Many officers in the division thought this would be a senseless

waste of human lives. Many recognized the final defeat for Germany was

inevitable and saw the only sensible solution as being an organized surrender.

On March 10, several division officers, including Colonel Thom, conducted

a meeting at Bad-Essen. They all agreed the division should surrender and

only sympathetic colleagues should be informed of the plan. Colonel Thom,

Chief of Staff for Division z.V., blocked Kammler’s ordered conversion

by simply delaying the reorganization of troops for the required battle

groups.

It was understood among all that the idea of surrender should not be mentioned

to SS General Kammler. It would have been suicide to do so. Kammler’s fanatical

attitude could not be reasoned with, and any suggestion of surrender would

bring an immediate death sentence. Kammler had already given the formal

order to reorganize the rocket troops into infantry regiments, and a few

weeks afterward, he made a speech before the regimental and battalion commanders,

giving wild battle orders. Soon after that, Kammler disappeared from Division

z.V. affairs altogether. Colonel Thom reasoned that if the division surrendered

as a whole, the Allies might be interested in employing some of the highly

trained V-2 specialists with their practical field experience for development

of rockets of their own. He believed, correctly, the Americans and the

British would not want the German rocket troops to fall into Russian hands.

Thom was then called back to Berlin at the end of March. It is unknown

if his confidence was betrayed after he sought support from higher echelons

in Berlin, but for whatever reason, he was relieved of his post. It looked

as if the surrender to the Western Allies might not happen.

On April 10, British forces discovered several V-2s on railway wagons when

they captured a large munitions factory eight miles southwest of Nienburg

near Liebenau. As the Allied push from the west drew closer, the leftover

remnants of the SS 500 began a disorderly retreat to the area near Göhrde

on the west side of the Elbe. In the following days, Battalion 836 (Art.

Reg. 901) moved to the marshaling areas east of the Elbe River where they

were joined with Battalion 485 (Art. Reg. 902) and a portion of Battery

444 near the area of Dannenberg. The V-2 division, which converted into

a Panzer Grenadier Division, was now at the disposal of the German 41 Army

Corps under Lieutenant General Rudolf Holste.

The individual soldiers of the rocket batteries believed their V-2 mission

to be an important one. They were disheartened by the rapid retreat and

sudden change in their situation. The war diary of the Battalion 836 (Art.

Reg. 901) stated on April 8, “With all of our specialized equipment destroyed,

the long-range rocket group has lost its character as an elite unit. Time

is up for Gruppe Süd and the employment of the V-2. We are now nothing

more than an ordinary infantry combat group.”

By the middle of April, the V-2 division, under command of the 41 Army

Corps, crossed to the east side of the Elbe River near the town of Dömitz.

As part of a motorized division, they were assembled in the area of Lenzen,

ready for deployment against the Russians. The unit was then positioned

in the area northwest of Fehrbellin, northwest of Berlin, east of the Elbe

River. Years earlier, this had been the battleground where one of the most

crucial victories in Brandenburg history had been achieved. But in 1945,

it was the place of a desperate struggle, which saw the end of greater

Germany. On April 26, 1945, the acting commander of the division, Lieutenant

Colonel Schulz, former commanding officer of Group North, was persuaded

by SS Lieutenant Colonel Wolfgang Wetzling to sign an order issuing authority

to open surrender talks with the Americans. Before this could occur, once

again the division found itself with a new commander when Schulz was relieved

by the young Colonel von Gaudecker.

Colonel Wetzling did not give up. He discussed the surrender plan with

several staff officers of the division. One of them, Major Matheis, agreed

to go with Wetzling to see the new commander of the division. During a

short meeting on April 29, Colonel von Gaudecker agreed to the surrender.

The plan was discussed in detail with the wishes of the division written

down. Wetzling and Matheis would act as emissaries accompanied by a signals

officer, and the arrangements would be transmitted back from the Americans

on a special wireless wavelength. On the night of April 29–30, von Gaudecker

gave two signed papers, one in German and one in English, to Wetzling and

Matheis. They received an order for fictitious duty in the area of Lenzen

in case they were stopped by German security patrols. The three men started

off into the darkness to find the Americans.

The next afternoon, they reached the banks of the Elbe River, close to

the small village of Wootz. Despite carrying a large white flag, they were

met with mortar fire. Major Matheis was slightly injured by shrapnel. After

continued shouting and waving of the flag, they finally got the attention

of some American soldiers on the other side. Several hours later, the Americans

transported the emissaries across the river and brought them to the local

American headquarters. Later they were blindfolded and taken to another

headquarters. There, talks began between the German emissaries and 15 officers

of the U.S. 29th Infantry Division. American Colonel McDaniel presided

over the talks and told the Germans he was authorized to receive their

declarations.

Colonel Wetzling announced the readiness of the V-2 division to surrender

en masse, unconditionally, provided an assurance was given that members

of the division would not be handed over against their will to the Russians.

McDaniel replied that the unconditional surrender of the entire V-2 troops

was accepted and that the members of the division would be treated according

to the Geneva Conventions. He was, however, not entitled to give further

assurances. The emissaries further declared that the V-2 division would

also bring with their surrender the goodwill to cooperate in the further

development of the rocket for the good of the Western Allies. Colonel McDaniel

agreed that the surrender of the V-2 division would be kept secret to prevent

reprisals against the families of the division’s officers. The declaration

was accepted by the Americans and forwarded on to the higher American authorities.

Colonel McDaniel said the division should cross at the same point near

Wootz. Boats of all kinds, including DUKWs (amphibious trucks), would be

in position by the morning of May 1 to ferry the division across the Elbe.

It was not known how long it would take for the V-2 division to arrive,

but the Germans were instructed to assemble near Lenzen and to move from

there in a line with every tenth vehicle carrying a white flag. At the

crossing point, four white flags were to be erected 50 meters apart from

each other. The Germans were assured that their movements would be safe

from American fighter aircraft. Colonel McDaniel asked for all V-2 equipment,

special vehicles, and V-2 documents of any kind to be handed over to the

Americans. The Germans stated that all equipment of this kind was destroyed

when the V-2 troops retreated from the operational launching sites.

Without any sleep, Wetzling and Matheis returned to their division headquarters.

They arrived late in the morning to find new difficulties had arisen. The

situation had deteriorated considerably because of Russian advances nearby.

Colonel von Gaudecker and Major Schuetze were in the middle of giving tactical

commands to units battling Russian forces. Von Gaudecker said it was impossible

at that time to withdraw the division from its positions. The situation

became even more chaotic when reports of a Russian tank breakthrough near

Fehrbellin reached the headquarters. Wetzling and the other officers convinced

Von Gaudecker that the only solution was to move the division as quickly

as possible to the river crossing point. As Russian aircraft circled the

area, Von Gaudecker quickly signed an order to the regimental and battalion

commanders instructing all units of the division to assemble in the area

of Lenzen. The units were to stay intact, and anything pertaining to the

V-2 rocket and its components, as well as any converted special vehicles,

should be brought along.

While negociations were being conducted, the former rocket soldiers, most

of whom had no formal training as combat infantrymen, held the line as

best they could. There had been no time for combat training before the

soldiers were thrust into the middle of the fight. Nonetheless, even without

the benefit of coherent leadership, they succeeded in repelling many attacks.

Each man did his best and the division managed to hold each section of

the line. In the east the German lines had endured constant Russian attacks.

From the west, advancing American divisions caused a critical situation

and Division z.V. was challenged from the rear. As the artillery bursts

were falling, an order came from regimental headquarters that stated—

“All troops should immediately disengage the opponent and travel to the

area of Lenzen, near the Elbe River. Our surrender to the western Allies

is agreed upon. In addition, all existing V-2 material and documents are

to be transported and surrendered.”

That evening as vehicle after vehicle arrived in Lenzen, the battle sounds

were all around the division. Fires were visible in nearby villages, and

the V-2 division was running out of time. Major Schuetze was in command,

as Colonel Von Gaudecker had traveled to the 41 Army Corps headquarters

to inform them of his decision to surrender to the Americans; there he

was promptly arrested. Schuetze had not arrived in Lenzen because of car

problems, and absent of any divisional commander present, none of the regimental

commanders wanted to take responsibility to order the columns forward to

the Elbe at Wootz. Already security patrols had passed by and asked about

the destination and purpose of the movement. A fictitious explanation was

given that seemed to justify the move, but it was evident the patrols were

becoming very suspicious. As night fell, it was clear no movement could

take place before the early morning hours of May 2.

The westward-route on which the division had been marching was overcrowded

with vehicles, as well as civilian refugees. Everyone had the same goal—to

escape from the Russians. The stream of humanity grew larger each hour

until it was up to three columns wide at points. Motor vehicles in one

column, horse carts in the next, with those on bicycles and on foot in

another column. The V-2 division made up only a small portion of these

flooding masses. All along the roads Russian fighter aircraft bombed and

strafed the fleeing Germans repeatedly. Some wondered if they would ever

escape to safety. On the horizon in the east and south large smoke plumes

could be seen rising into the sky. The Russians were advancing quickly

following the collapse in German resistance. After the V-2 division passed

the town of Perleberg, the Russian fighter-bomber attacks ended. Subsequently,

American aircraft were flying over the roads providing protection to the

refugees.

Major Matheis took charge and ordered the continued advance towards Wootz.

On the morning of May 2, 1945, the first units of the V-2 division arrived.

Colonel Wetzling was in the lead vehicle directing the column to the correct

crossing location on the river. American posts for disarming the surrendering

Germans were set up on the east bank of the Elbe River. The Americans provided

translators to help in directing the flow, though the crush of people and

vehicles trying to cross the river created chaos. For awhile, it was everyman

for himself. The troops of the V-2 division were mixed in with civilians

and other German Army units as the Americans made sure every transport

was filled to capacity. Storm boats of the U.S. 121st Engineer Battalion

were used to ferry the soldiers, while the Gorleben Elbe ferry moved the

vehicles.

V-2 division soldiers had no idea if all of their comrades had made it

across the river. Only a few of the division’s vehicles were ferried over

the river that day, but more would be brought over later. The ferry service

ended late that evening, around 11:00 PM, with many refugees remaining

on the east bank of the river. The majority of the rocket soldiers had

successfully crossed the Elbe, but the members of the division were saddened

to learn a few comrades had been left in the rear. Behind them, the smoke

pyres were subsiding, signaling the Russians were quickly advancing towards

the Elbe. If not for the efforts of these few division officers such as

Colonel Wetzling, the whole of the V-2 division might have been slaughtered

or taken into captivity by the Red Army. Thus, with the capture of the

V-2 division, the German A-4/V-2 ballistic missile campaign came to an

end. At dawn the next day, word spread among the V-2 troops of Hitler’s

death, which was announced overnight.

Of course, given the situation, the move of the division to the Elbe River

was very difficult. Confusion was everywhere, and the constant threat of

air attacks made any movement extremely difficult. Nevertheless, the majority

of the division made its way to the crossing point in good order, arriving

on the night of May 1-2. During these last few days, it appears the remnants

of the former SS Werfer Battery 500 were not among the V-2 troops surrendering

at the Elbe. During the last days in April, most of the former SS 500 units

were cut off by a Russian attack in the area of Friesack. Assigned to fight

with another German division to the south, the Nebelwerfer batteries expended

most of their ammunition in skirmishes against Russian forces. However,

some of the fractured SS 500 groups, instead of joining in the useless

fight against the Russians, intentionally remained “lost” in an attempt

to survive the last days, until they finally surrendered in small groups

at various locations. Only a few of these men managed to make it through

to the crossing at Wootz.

|

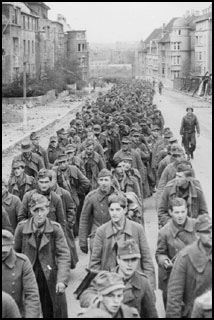

Units of the V-2 division marched in perfect order into captivity. Led

by their officers, the men were allowed to carry only hand baggage and

blankets. Further up the west bank they were again checked for weapons

and a portion of their personal property was removed before marching again

to a collecting station. The rocket soldiers queried each other about their

comrades. When a straggler came in, he was greeted and stories of the terror

were recounted. All were thankful to have achieved relative security. American

trucks arrived intermittently, beginning on May 2 and ending on May 4,

to transport the V-2 division members to the rear. The roads again were

swamped with traffic and movement was slow at first. After the Americans

ceased to translate for the Germans, there were rumors circulating that

reported the Russians had demanded the return of the V-2 division. Urgency

was needed and the convoy soon raced along the roads. The trucks were dangerously

close to one another; nevertheless, the black American truck drivers were

experts at navigating the overpopulated roads and stopped only once before

arriving at Camp Herford after nightfall.

As the trucks pulled up and stopped, the headlights lit up a large field

in the middle of a sports stadium. The American soldiers then barked commands.

The trucks were emptied and the Germans were herded like cattle in a line

towards the field. Scattered over the field were humans of all categories.

People of all ages, all military ranks and services—even civilians, including

women and girls—were seen huddled in groups. |

|

Even though it was so crowded that there was no place to sit, continuous

throngs of prisoners were pushed into the area. There was nothing to eat

or drink and the existing latrines were in sufficient. The conditions were

abhorrent. After nightfall it was easy to hear the despair. The lunatic

calls echoed into the night. Spotlights scanning the crowds and machine

gun bursts would wake those fortunate enough to find sleep. The Military

Police used brutality—fists and batons—to control the crowd. The remaining

property of the captured Germans, such as compasses and watches, was confiscated.

Divisional Judge Wetzling began inquiring with American authorities as

to the whereabouts of the members of Division z.V. He also sought to have

the rocket troops removed from their current circumstances at the camp.

Wetzling was asked by the authorities to locate and select about 100 V-2

guidance specialists, crews and technicians, but given the current state

of the division, this was extraordinarily difficult. Those selected would

be removed from the division for an indefinite period. On May 7, 1945,

the chosen specialists were moved from the masses at Herford into a nearby

public swimming pool. That evening one of men cooked a magnificent pea

soup, their first warm meal in days. On May 9 the Germans were placed again

on trucks. The men wondered—what was their destination? Were they going

to America?

The trucks rolled on past the Dutch border towards Belgium. In many villages

the streets were full of citizens, many still celebrating V-E Day. As the

convoy of trucks drove through the many towns along the route the Germans

were jeered and pelted with all varieties of projectiles. Flowerpots, along

with beer and wine bottles, rained down on the men in the trucks. The worst

of this abuse occurred as the convoy passed through the dense streets of

Brussels. As the drunken crowd screamed their insults, the Germans remained

expressionless. After driving around Brussels for hours, the convoy finally

rolled to a stop at another camp. This former brickyard was a British camp

and the rocket men wondered if they were brought to this new location intentionally

or by mistake. They were not given a reason. Over the next few days the

Germans formed together the basic command structure of their new guidance

group. Made up of the existing men of the former V-2 battery, the new troop

was commanded by its oldest officer, Lieutenant Colonel Weber, along with

two staff officers and the Divisional Judge.

Their stay in Brussels was short. On May 11, 1945, the Germans were rousted

from their meager accommodations and again packed onto trucks in the hot

midday sun. After driving west for several hours they arrived at another

POW camp near Brügge. The rocket troops were housed with the regular

prisoners of war, but were not separated from one another. The long days

at Brügge were very monotonous. The Germans occupied their time in

camp by attending lectures concerning art, literature and music. The soldiers

attended theatrical plays put together by the prisoners of the camp. They

retained the impression that the British had no future plans for them.

However, on May 13, 1945, a British officer arrived at the camp and began

asking technical questions about the V-2. Per his request, the Germans

prepared a memorandum describing the general overview of the rocket and

its operation. The papers were given to the officer along with an organizational

chart of the V-2 division. After British interrogators returned several

more times, the Germans began to realize that the Allies were greatly interested

in the V-2.

On June 1, 1945, the men learned that they would be transferred once again

to a new camp. The following morning the men of the V-2 command were served

a large breakfast of milk and fruits. After formalities, several trucks

arrived to transport the Germans—trucks that were much more comfortable

than the ones previously. Two days supply of food was brought with them.

The men questioned again, what would be their destination? There was a

rumor of going to Germany, namely Koblenz. Around noon the convoy passed

again into Brussels. This time the drivers took a more discreet route and

they entered substantially unimpaired. Near the outskirts of the city the

trucks came to a stop at another POW camp. The Germans hoped that this

would be just a short stay for food, supply and rest, but they were soon

disappointed. After being ordered from the trucks, an NCO barked the roll

call. Then, as they marched into the fenced-in internment camp, the men

were shocked to see tattered tents sprawled in the middle mud covered field.

The dejection felt by the men, who only the day before had been well situated

in the Brügge camp, was indescribable. As the men received their evening

meal, which was only a thin marmalade soup, they felt like they were once

again being treated as criminals.

A meeting was called, led by a British major, who informed the Germans

of British plans to launch V-2 rockets near the German town of Cuxhaven.

A few days later, a certain British general traveled to the camp to ascertain

the technical abilities of the captured German rocket troops. The British

were also interested in the specific requirements pertaining to preparation

of a firing position. It was suggested that the specialists of V-2 division,

which had all been selected earlier based upon their technical and field

knowledge at the Herford camp, would be used to conduct the firings while

under British supervision. The Germans offered a delegation of men to travel

to the launch area for inspection, but this was denied.

On June 30, 1945, all of the men were marched from the camp to a transit

store. There was a rushed, but thorough, medical examination before the

Germans were loaded again onto trucks. The convoy traveled through Antwerp,

into Holland, passing Tilburg and then on to Arnhem, where the men were

given temporary accommodation for the evening in a Dutch schoolhouse. When

they arrived a rowdy crowd of Dutch citizens surrounded the trucks, but

the British soldiers of the convoy took control of the situation and quickly

dispersed the crowd. The next morning they traveled on towards the German

border and crossed at Oldenburg. Near Bremen the British transport officer

had to ask some American soldiers for directions, but finally they arrived

at Cuxhaven after midnight, and the Germans were billeted for the night

inside an old fishery. On the morning of July 2, 1945, the Germans were

brought to the British camp nearby at Altenwalde.

The complex of buildings and shops was all that remained of the former

Krupps gun testing range. After a good cleaning, the former barracks of

the Kriegsmarine provided friendly and comfortable accommodation, particularly

when compared with the previous camps in Belgium. In the surrounding sheds

they found some badly demolished tools and equipment which had belonged

to the previous facility. The Germans had already been told of the plans

to refurbish the shops and equipment in preparation for the upcoming British

tests, but it was certainly clear—new procurement would have to come before

any visible work could be carried out. With great difficulties, Major Matheis

organized the operating administration of the V-2 troops. There was literally

nothing available to them. Only a few pencils existed and the men were

forced to create their own rulers and compasses.

|

However, the Germans wanted to begin quickly, thinking the sooner they

conclude their tasks, the sooner they might be released to check on their

families. Using the former jargon of the wartime operational batteries,

the group took the name Versuchskommando Altenwalde (AVKO). The group is

commanded by German Lieutenant Colonel Weber, former commander of Artillery

Regiment (motorized) 901 (Battalion 836), Division z.V., Group South. The

name of the British project is given as Operation Backfire. The V-2 men

were supplemented by necessary numerous auxiliary workers who came over

from the 736th Labor Camp. At the end of July the command was substantially

expanded with the addition of a large number of civilians. AVKO had requested

numerous scientists and skilled workers from Peenemünde and the Mittelwerk

to supplement the existing workforce.

Director Lindenberg and Professor Wierer headed the technical shops, while

Arthur Rudolph directed the manufacturing department. Eventually, an almost

identical arrangement was achieved, which mirrored the wartime technical,

manufacturing, and operational procedures. Difficulties between the shops

were worked out quickly, as the Germans realized the necessity of reaching

the common goal. |

|

When the members of the V-2 division arrived in Altenwalde they came as

POWs. But on July 20, 1945, the kommando received the status of “Disarmed

German Personnel” and were subordinated to the instruction of their own

commanders. They were allowed to move about freely and received military

pay from the British for their services, with extra pay promised on the

completion of their work at Cuxhaven. Even though their work had begun

under the poorest of conditions, it wasn’t long before conditions improved.

A spacious assembly shop and an impressive testing tower were just a few

of the improvements built by Royal Engineers. New concrete roads were constructed

with extensive work near the actual firing position, which is situated

in the forest just offshore. At this location large concrete bunkers for

firing control and observation are also built.

Each day at 5:00 PM, after a rigorous day of work, the siren announced

the end of the shift. The men flowed out of the offices and shops and walked

the road to their quarters. The camp became “home.” This sentiment was

reinforced in those who were allowed to travel on official business to

other areas of war-ravaged Germany. At Altenwalde, a place untouched by

the storm of war, they felt a sense of community. In September the work

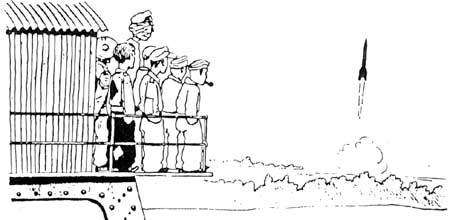

of the Germans was coming to a conclusion with a total eight V-2 rockets

being produced. The date of the first firing was announced as September

27, 1945. A nervous tension was felt experienced by everyone as the day

approached. The first rocket was towed to the firing position a few days

prior to launching. It was under a storage tent and protected by a British

special guard.

Beginning a few days late, the first rocket was finally ready. October

1, 1945, dawned with gray skies and increased tension in the camp. Everyone

questioned whether of not the launch would occur this day. The English

officers express their doubts, but an attempt was mounted anyway. The results

were not satisfactory. After two failed ignition attempts, the rocket had

to be defueled. However, in the face of this the German firing crews were

not discouraged. Many delays such as this had been experienced by the firing

crews during wartime operations; nonetheless, some of the British officers

condemned the device as too complicated.

October 2, 1945, presented a fair day with sunny skies. Confidence was

high and the launch went off perfectly. The rocket was seen rising into

the blue sky all the way through Brennschluss. Rejoicing and emotional

release swept through the German command. This was matched by the enthusiasm

of the British soldiers. Sincere words of the acknowledgment were given

to the V-2 division soldiers.

During the summer of 1945 British authorities first anticipated that at

least thirty V-2 rockets would be assembled for the Backfire tests near

Cuxhaven in Germany. However, because of scarcity of materials, only eight

rockets were assembled, and of these, only three were launched. If one

can believe the rumors that were circulating in July of 1945, more than

200 V-2 rockets were transported to Altenwalde and the excess material

was sunk in the bay at the conclusion of the tests, but documents confirming

this have not been found so far. At the conclusion of the tests the former

men of the V-2 division filtered back into German society to begin new

lives. |